SPX Sessions: Ben Passmore

Back in September, I had the pleasure of attending the Small Press Expo (SPX) in North Bethesda, Maryland. With a focus on small and independent publishers, SPX is a convention brimming with creativity and diversity. While I did not get to see Cartoon Network’s Rebecca Sugar (Steven Universe, Adventure Time), I did get to speak to award-winning creators like Nate Powell (March, Swallow Me Whole) and Ben Passmore (Your Black Friend, DAYGLOAYHOLE).

Today, I will be focusing on my interview Passmore, with whom I discussed a variety of topics such as his comics journey and art style, the diversity of the industry, and politics. The classic fighting game Shaq Fu may have also come up in our chat. Maybe.

Note: The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity.

Okay, I am here with Ben Passmore, the award-winning author and creator of Your Black Friend and DAYGLOAYHOLE. Ben, how are you doing today?

I’m great.

How is SPX going for you?

It’s good! Every year it gets a little blacker. I think that the things that I looked for when I was starting out are different from what I look for now. As recent as maybe three years ago, four years ago, I couldn’t get a table. I was walking around just trying to trade comics. And now what I’m looking for is, even though the comics community isn’t my primary community, the more particularly black cartoonists, just general creators, are out here, the more excited I get, you know what I mean? And it’s less about me trying to break in or find a job. So it’s exciting for that. There’s that moment in the [Ignatz] Awards — I was talking to you about this last night — about where it’s like they let me talk for forever. And then Richie Pope got Outstanding Artist. And I was like, “Oh, shit! We takin over!” That was great, yeah.

Yeah, last night, that was fantastic.

[laughter]

There was something we chatted about yesterday. You mentioned change. “Change is coming” — that the industry is changing. How have you seen the industry change from when you started up until this point? Can you speak on that?

Well just generally, I think a combination, really a combination of Trump, and then a lot of just sort of general black media came out, and I think that the comics industry is interested in our stories right now. I am not optimistic enough to think that that will stay that way or that it is much more than recognizing a market. But, for now, the comics industry, at least my experience of it, there’s a lot more people pursuing me and, I see, pursuing my peers for work. So just like on a “get the bag” level, there’s more opportunities for us, you know what I mean? And, incidentally, more opportunities for us to tell more different stories about ourselves, you know what I mean? So that’s exciting. I don’t think that a couple of years ago that that was true. I felt like there would be one kind of story that was prevalent, you know what I mean? I don’t know if you were part of the conversations but you know like if Trump gets ousted next election, [the] industry might swing back.

You did mention that yesterday, that’s true.

The one thing I will say is that SPX is different than Dark Horse or something. SPX, I do see them responding to criticisms, wanting to accommodate necessary changes in the industry and I think that it seems to me that the changes that they want to make would be permanent and that the industry like it’s whatever… We still live in a white supremacist society, you know what I mean? They’re gonna feel… I think if another Obama type comes–you know, during Obama a lot of these people, there is a lot of entitlement, even in the left on their sense of desperation does not maintain… You know what I mean? And they’re pretty ready to believe that we have power and influence that we don’t necessarily have. The majority of my editors are still white… You know what I mean? That’s probably not gonna change. So yeah, so there are some good things right now, but I can imagine that’s gonna stay that way, and I’m sure there’s a conversation we can have about sustainability as someone who’s an anti-capitalist is also a complicated conversation if you wanna talk about maintaining an industry. I’m a feel kind of circumspect about it. [laughter]

That was actually on my list of questions. Particularly ’cause I feel that a lot of times it’s really important to be able to control your own narrative. So I did wanna ask you about editorial processes. You did mention that a lot of your editors are still white.

Yeah.

You don’t think that’s gonna change. But, also, in sustaining an industry, you do seem to be someone who was able to create a space for yourself and to do the same and help other comic creators and young creators of color. Would you agree with that sentiment?

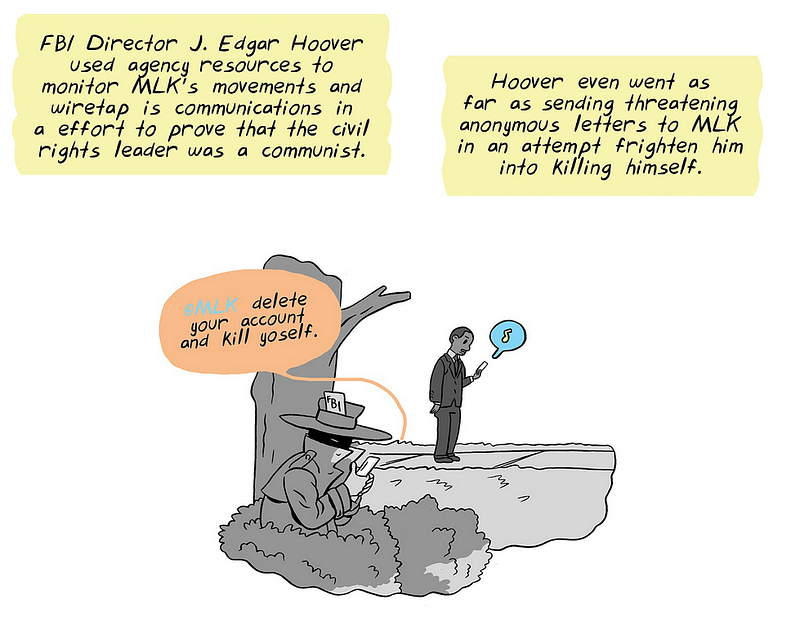

I don’t know, I mean I appreciate that narrative! [laughter] Yeah, I don’t know. I made comics for a long time, and no one cared and I didn’t get a lot of money for it, and then I was given jobs. I think, fortunately, I was in my 30s and I have been a long time squatter and punk. I was not afraid — I’m not afraid to lose any job I’m given, so in that way, I just continue to make what I wanna make for the most part. I mean obviously for us, working in a mostly white industry, there’s things you put up with, you what I mean? There’s a level of token-ism that you’re aware of that your editor is not aware of. Maybe there’s places that I should push more and be more vocal about but, for the most part, I say “Whatever,” and, fortunately, no one has fired me. And no one is really for the editing, ’cause there’s white washing that happens. Because comics was so white, I think I wrote with white people in mind a lot and I’ve been doing that less and less. Sometimes when I’m edited, I’m writing as if the reader is black, and has this mutual understanding, and my editors would be like “This doesn’t make sense” or “We’re not sure if this is necessarily true.” I did an article about MLK in which I sort of just mentioned that the FBI…

COINTELPRO?

Well, there’s COINTELPRO, but also [the FBI] had a hand in his assassination, you know?

I know what you’re talking about.

So I was like, “Yeah, that’s a given. This is an open secret. They settled out of court.” But you ain’t settlin, you know what I mean? If you didn’t want any shit to get out, you know what I mean? And my editor’s like “Well no, there’s no receipts for that” or whatever. And I was like, “If this was a black audience this [would] not be an issue.” So it is what it is.

What drew you to this medium in the first place? What drew you to comics? And what inspires your stories?

Originally, I grew up in a really rural spot. I was really young — it was before the internet, and then it was early internet. I didn’t have a TV for a lot of it. I had a Super Nintendo, but was broke as hell, so I had like two games for it, which got old real quick.

Which games?

I had Donkey Kong and Shaq Fu.

Shaq Fu used to be the game! [laughter]

Yeah, I was definitely maxin’ niggas in Shaq Fu. [laughter]

And there was no comic shop, there was a drug store that sold like five titles and there was a video store that sold three. But I got really into comics ’cause every week there’s new shit. It was accessible, and I never could afford it, but I would go into the store and I would sit down, and I would read as fast as I could before they kicked me out every single week. And my mom was an artist, and she was very supportive. So I was just a frenetic drawer. I mean, every moment! I was bad with people, I was bad at school, I was bad at sports. So I was just very much in my own little world just frantically drawing characters and stuff. So that’s how it started out, and I think that’s something that helped me.

One — even though Todd McFarlane is terrible — but when I was coming up, “Spawn” came out and I was right there for the gritty shit. He was black, that was great, and the person that gave me issue one of “Spawn” was also a black nerd. It was this dude that watched me as a kid. So, for me, I didn’t know about the prominence of white [people] or the whiteness of comics or didn’t even really think about it because my introduction into it was a very black experience. I kept drawing. I never thought about it as a career. I drew superheroes, but it was more — it was just like I needed to get it out. It was a very direct power fantasy. It was very direct escapism.

And then in high school, I got locked up for a couple of years. When I got out, I think that I got radicalized while I was institutionalized, and I think that I felt a need to not escape and write grounded stories. I was reading manga, but I was also reading Optic Nerve and a lot of the indie stuff, and I was like, “I wanna write about me. I wanna write about the world.” It was the Bush administration, and that’s really what’s driven me since then is this desire to put ideas together in a way that makes sense to me, for me to figure stuff out.

I got involved in an anarchist community, the punk community, and for a long time I was just making comics for people in New Orleans. The first issue of DAYGLOAYHOLE there’s a lot of, lot of references that I’m like, “People will like that book,” and I love it. [There’s] a lot of shit that only makes sense to people in New Orleans. But only a small percentage in New Orleans. And I liked that I could write about something like New Orleans. There’s a lot of creativity there. It’s ten hours from every other major city except for Baton Rouge — and ain’t no one really goin’ to Baton Rouge. So it’s this little microcosm. What’s just happened is that the circle has expanded. Who I’m speaking to has sort of expanded, but it’s in the same spirit. It’s me talking to you.

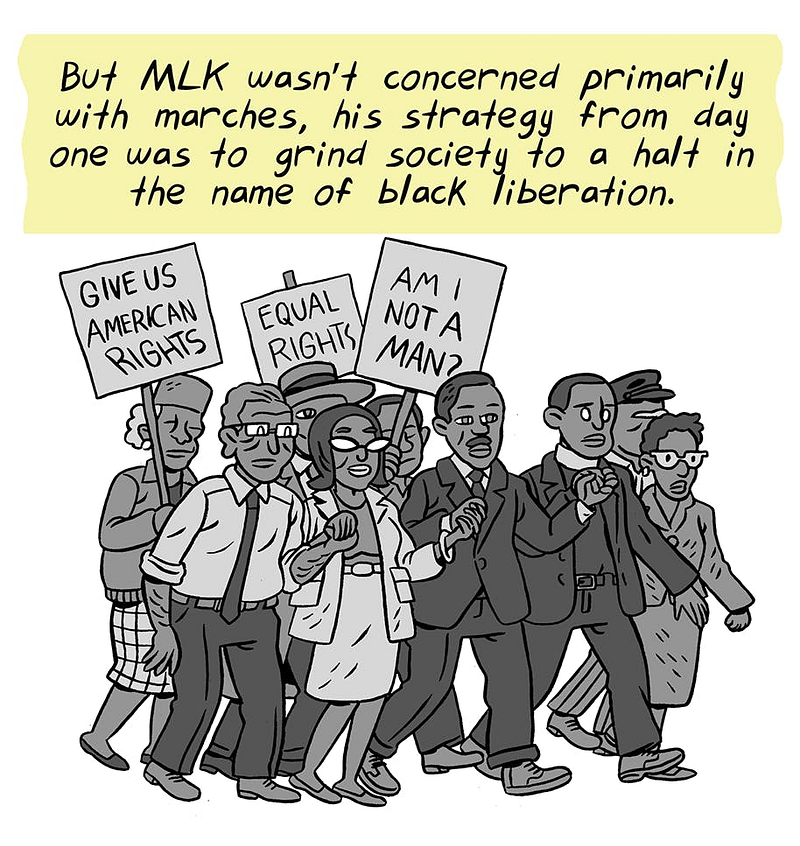

Particularly for The Nib stuff, I felt really important — post-Trump — to be someone that’s not advocating for a respectability narrative, because I resented the revisionism around the Civil Rights era, where people take a lot of the antagonism out of the sit-ins and make it very performative. And also sort of make references to the Panthers, but don’t acknowledge that the Panthers transitions — or, in some ways, schisms — into the Black Liberation Army, and niggas out here robbin’ banks. Shootin’ cops. But also feeding people, and that there are a lot of different ways that people participated in the liberation. And today, that’s important. It’s important for people to accept the variety of tactics for this crazy era of very popular fascism [and] white supremacy right now.

So for me, when The Nib was like “Do you wanna write about the stuff” it’s like, “Okay, I’m a write me as a black man right there when Antifa is punching a Nazi.” And to talk about the ideas, ’cause I wasn’t really reading other people do that. And anarchists generally are not super great at explaining in a coherent way, like what they’re about and why they do things.

It’s interesting you bring up the Panthers, ’cause in my understanding — I love history, but a lot of times it gets tricky to piece together what did or didn’t happen. My understanding is that there were multiple schisms because there was the original Panthers with Huey Newton and everyone who founded it back in Oakland. There was a schism between them and the younger New Black Panther Party.

Yeah.

Which is interesting because, if you look at the Southern Poverty Law Center, they actually designate the New Black Panther Party after the schism — the more radicalized one — as a Black extremist group. But they don’t for the original Black Panther Party.

Interesting.

And the Black Liberation Army, I think is also [designated] as a black extremist group, but not the original Black Panther Party.

Yeah, yeah.

And I remember looking at this when people were asking “Why isn’t Black Lives Matter considered a hate group?” and the head of the SPLC put out a giant op-ed about it, and he’s just like, “This is why.” He was like, “Yeah we have black extremist groups, but Black Lives Matter is not one of them. And neither is the original Black Panther Party,” and things like that. I found that very interesting, to have non-government organizations that are really trying to just keep the record straight as much as they can. And it’s just one entity. Shifting gears a little bit: Talk to me about you getting locked up. What happened?

Well, I went to Georgia — went to Stone Mountain — and there was a Klan rally. I think it was Hitler’s birthday, and an organization called the All Out Atlanta had called for people to come. And what can I say? So, I felt just as a Southerner, as a carpet bag Southerner, as a Northerner who adopted the South as my home, I was like, “I’m a go.” Not a very interesting story, but I was in a group of antifascists. I’ve never been a member of Antifa, just “As a black man that is not trying to fuckin’ see some white people out here going unopposed, I’m a roll with them.” And we had masks. We had masks because the police take video. We had masks because Nazis and Klan members take video. And they’ll come and find you — and they can come and try if they want. But that was the initial reason. Georgia has a law there in place against masking — specifically for the Klan — but they use it —

Against everyone…

Yeah, yeah, primarily in the last bunch of years to target anti-fascists. And a lot of the people on the left will cape for the cops and say, “Well, you’re out here hiding!” But it’s stupid, it’s ridiculous. Of course, you gotta hide your face. It’s not like it was a couple of years ago — and that might have been the Southern Poverty Law Center, I forget who it was. They put out an article about a white supremacist group infiltrating police. I’m not out here believing any cop has my best interest. I got roped up by a black cop. That’s a whole other level in the way that black police help reinforce white supremacy. So they grab me for having a mask and I’m ignorant. And I ran away. But I used too much breath making fun of them while I was running and I got tackled. ’Cause I played football in high school, but that was a long ass time ago.

So it’s like “Yeah, I can run! Oh, shit!” [laughter]

I got tired real quick. Yeah, and so it was fine. I spent seven hours in jail, which is quick time in jail, and All Out Atlanta had a lawyer and bail for me within a couple hours of me getting arrested. And it was great, you know what I mean? I had been a teenage criminal, but I had never spent a bunch of hours in jail. That was a whole thing. There’s a lot of sensationalism around Antifa, and I think that talking about their assault on fascists is important because it is an important strategy, but also people don’t talk about the infrastructure they build around supporting people.

I’ve been involved in radical politics for a long time, but a couple of people [who] got locked up weren’t. And it means a lot, as someone who grew up with people that were in and out of jail, it’s a whole different thing when you get outta jail there’s someone to pick you up. They got a sandwich for you, and they tell you they got a lawyer for when you gotta go to court. That’s just very important, and I’d love to see radical communities extend that outward to people who don’t necessarily identify as political agents, but very much are.

A bunch of years ago, I picked up a friend of mine who got locked up — actually just harassing a cop that was harassing people. And he had made a friend who was like an older, black man — maybe in his 50s. I gave them both a ride back to our neighborhood, and my friend had explained anarchism to him, but I think the dude didn’t totally get it. He was like, “Oh it’s cool. You came to pick up your friend.” I was like, “Well, you know, anarchists, we try to help each other out.” He’s like, “Shit, if I knew that anarchism meant you get bailed out and driven home, I would have been an anarchist years ago!” [laughter]

Talk to me about your art style. How did that develop? ’Cause the way that you draw all the characters in the environment and the lines are very unique. I kinda call it “wavy”, maybe like Silver Surfer wavy, but definitely, it seems like a very wavy art style. How did that develop?

So that’s a good question. I was heavily influenced by a lot of the — when I was young — there was the superhero stuff here, and I was reading manga, and I was watching anime — and I was not good enough to recreate that. [laughter] I got really inspired by underground comic stuff, even some of the shit that I was like “Actually, this is really racist.” I had to leave it, but yeah, a lot of the underground stuff ’cause it was, like, drip and weird and cartoony. And the range of what was acceptable mark-making was much wider. This is the 90s, this is [Rob] Liefeld, this is Jim Lee. That was what I was watching, I was like, “I don’t think that’s it for me.” I tried — I was terrible at it.

But I don’t know, I drew really frantically, and I went to art school, and I was awful. I was still trying to draw like Todd McFarlane, and honestly, what I did is I copied things that I liked for a while, and then one day it seems like it all sort of turned into this consistent style. Which is usually what I suggest to people that are trying things out. ’Cause even if you try to copy it’s gonna go through the lens. Your style is a combination of your ability and your shortcomings and your vision.

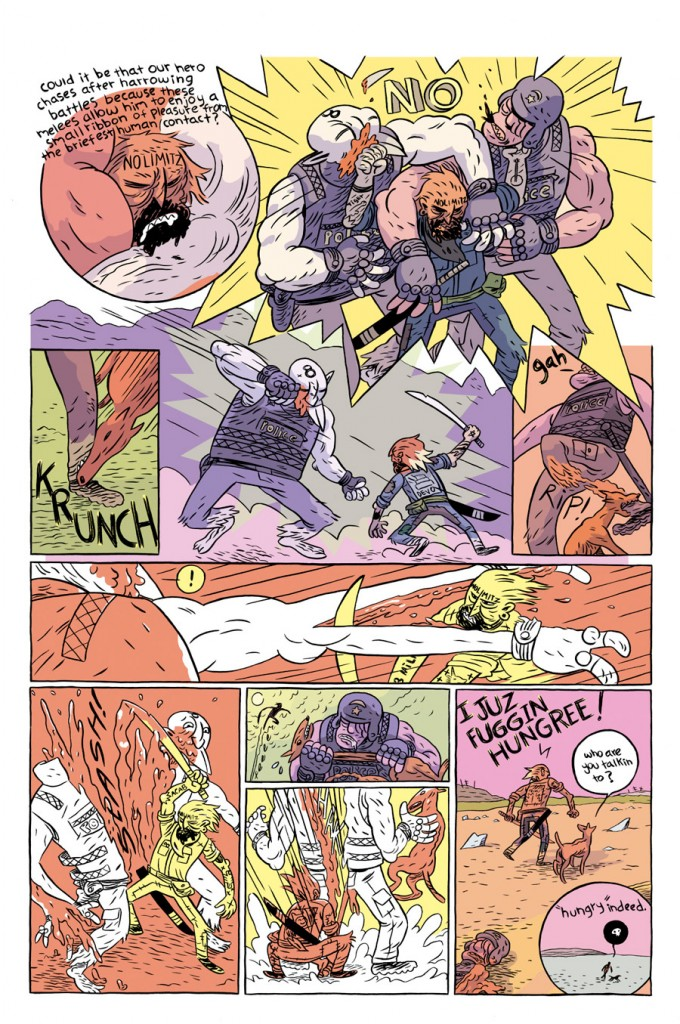

What you want to draw is refracted through your physical ability and limitations and your brain and your weirdness. So what has become my consistent style, is like my aspirations. You refracted through my limitations and it is goopy! It’s interesting doing non-fiction stuff now, ’cause before, I was doing stuff like DAYGLOAYHOLE which is filled with monsters and violence blood and guts and vomit — and I love drawing that shit, you know what I mean? So, drawing a march and politicians and stuff… I wish I could just draw them all vomiting. But I do like to draw viscous liquid stuff like that. A lot of cartooning is trying to make ink look like other stuff [and] make everything feel really tactile. That’s a big motivation of mine in drawing — whatever it is.

That’s a good point you brought up about the liquid viscosity and fluidity of the art style. I guess the “waviness” is because it seems very fluid. More like liquid. It’s ever-changing, not necessarily conforming. Which fits you! It makes sense.

I think also when I was looking at political comics — like early 2000s — there was this cartoonist named Peter Cooper who has a very angular, super 90s style. He even used a lot of stencils and spray paint and the work. He’s not dead, he’s still alive. I don’t want to talk about him like he’s dead. But when I started reading a lot of him is when I really dropped trying to do representative stuff, and really emphasized kinetic energy and weight. And I was like, “Even if I draw cartoony, if these bodies seem like they’re in a space or if they’re really moving,” I realized that that can create the illusion of a possibility. If it really feels like it’s in space or regardless that it’s got weird oval eyes that that will be convincing enough. So even though my characters kinda look like people, if someone’s getting hit, it looks like someone’s getting hit.

Yeah, the designs are abstract, but it’s not super abstract. It’s semi-abstract, which again, the fluidity of the line style, of the art style.

I see other artists that are obviously inspired by Mike Mignola. And it’s somewhere in between, it’s like that and the Adventure Time style. I think that I’m part of a wave a little bit. And I didn’t know that until a couple of years ago, but I see other artists and I’m like, “Oh yeah, we’re drawing from similar areas.”

Which is incredible, especially considering if you weren’t really dialed into it. You weren’t literally dialed in, but, maybe on a metaphysical level, you just felt it and you expressed it, and that’s how it came out. And all of a sudden you look around and you’re just like, “Oh, shit. Other people are doing something similar?” It’s interesting.

Yeah, both Richie Pope — who’s 32, I’m 35 — and Andrew MacLean, who I think is maybe, if not my age, maybe a little older — that’s my generation. I feel like we both have very similar touch stones even though our drawing is a bit different.

What advice would you give to anyone who is trying to create their own comics or trying to get into the industry? Obviously, you work as more of an independent, not necessarily trying to go with any of the big companies. But what advice would you give to someone who wants to get started — especially those who are young?

Acknowledging the hurdles. You can work really hard and never get the couple jobs that are out there in comics. And those jobs don’t pay a lot, so that’s a huge hurdle. It’s very, very time consuming, so you have to love it, you have to want to make it. And also you have to get over the fact that it’s not gonna be fun all the time. I read this great foreword by Chris Ware in McSweeney’s. Are you familiar with that? They did a comic collection, like a bunch of years back.

No, actually.

It’s good! I mean it’s a lot of the bald white dudes, you know what I mean? It’s like Charles Burns and all that. But Chris Ware’s output is amazing and he’s a humble person. He’s a humble white dude. But he talked about how miserable he is drawing comics.

I really appreciate it, because there’s this fiction that we’re all doing something we love — all the time — and it’s great, and it’s an adventure. And it’s not. Comics is really, really hard. And the only real answer for being part of comics is producing things. If you can’t finish something, then it kinda doesn’t matter how great the drawing is. You have to finish.

And the reality is, for indie comics, there’s no such thing as breaking in. The way my career looks now — it’s not very old. It’s, like, two years, maybe three years. And there was never a moment, there was never a contract or anything, where I was like “Oh I broke in.” You just lace together freelance jobs, you try to make as much work as you can, and one day you’re like, “Oh shit, that’s my whole rent paid.”

But, fortunately, the way it is, you can still self-publish your comic and get it out there and people will read it. You can still make a thing and have it really pick up. There’s a lot of possibility in the industry, just in terms of people looking at it. It’s an industry that loves new work, that loves reading. Yeah, it can be really frustrating. It was frustrating as a self-published person trying to get a lot of people to read, ’cause people do really wanna read phonographic stuff. What did I do? I guess I self-published a lot, I tried to go to shows, and I tried to get into anthologies. But I rode this wave before anthologies became a thing that people really cared about, and I still do. Everyone was trying to make an anthology and that helped out a lot.

You just gotta make work. One of the nice things about it, and one of the frustrating things about comics, is there is no road map. Every single person kinda [has] to figure it out. Certainly I would love people to make it way before I did, way before their ’30s, you know?

Everyone gets their shine when they get it though, right?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. End of the day, you gotta make work and make work that you love, that you wanna make. I think that’s the big thing. Not trying to anticipate a trend, ’cause when you do get the jobs, you gotta stay true to yourself. People are not gonna be excited by something that feels like soulless work. It’s hard. [laughter]

That’s a good point. I did have one last question. It’s not necessarily related to comics, but it’s something that’s been on my mind that I’m probably gonna be asking a lot of people — even family and friends. It’s definitely a loaded question, but: What is blackness and what does it mean to be black? To You?

Yeah, that’s complicated. I always feel weird saying this, but I do believe this that, primarily, blackness is a construction of whiteness. And blackness is a relationship to power, or a lack of relationship, but not in totality. But I think, for me, that was important because I think that — like a lot of people, for a while — I bought into a narrative of blackness and was responding to it a lot, rather than recognizing my own individuality. Also, as a mixed person from a rural place, it’s even more complicated, right?

’Cause coming up in the 90s, there was TV, and there was music. And they’re presenting — I don’t think I totally understood — a very particular, if not totally fictitious, kind of blackness. And then you feel like you’re responding, not just to that, but the white people that are watching that, putting that on you, you know what I mean? That’s been around for black people for a long time. It’s that two-mindedness, right?

Yeah, that double consciousness. So for me, black is having your culture annihilated and thriving anyway. Like, it was really cool going to the Caribbean. And that’s the history too, right? Like a strong physically, spiritually, personality-wise, just a strong, beautiful people that create amazing things. But what blackness is, specifically, that’s my journey, you know, particularly just as a weird person and a weird type of Black.

I mean, there’s a lot of us!

Yeah, yeah, it’s a big tent. I think one of my frustrations, just with the United States, is who gets the most money? A lot of this is white money, and they really only want us to tell some stories. I feel like we’re in a good time where we can tell more stories, more of our stories. You can be weird — Random Acts of Flyness is amazing. It’s a weird, weird show and really talking about a lot of different ways of being. So I don’t know, that’s a rambly, long answer.

Whatever comes to mind, man.

Yeah. Black is power!

FACTS! [laughter] Ben, thank you so much, man.

Yeah, yeah! Thanks for asking me! I appreciate it.